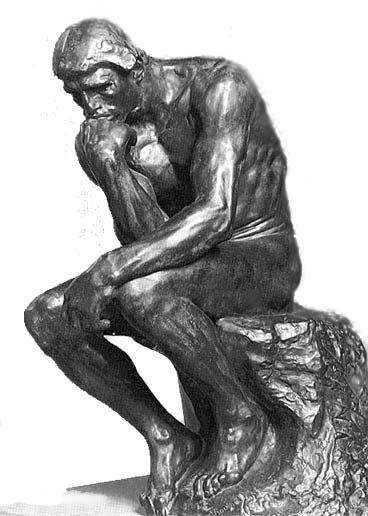

I’ve been thinking…Just what is an ESOP?

An ESOP, or Employee Stock Ownership Plan, is a unique, tax-favored employee benefit plan that can be used as an acquisition financing technique in a highly structured M&A transaction designed to provide liquidity to an owner of a business.

This primer will focus on the anatomy of a typical ESOP M&A transaction: the acquisition of a business owner’s equity securities by a Trust acting as a fiduciary on behalf employees of that business. At its core, an ESOP M&A transaction involves (i) a motivated seller, who initiates the transaction and arranges/approves (and pays for) all material aspects of the ESOP M&A transaction, including the fees of the buyer’s legal and financial professionals; and (ii) a sophisticated buyer (the Trustee acting as a fiduciary for the company employees) who negotiates the terms and conditions of the purchase of equity shares from the seller.

ESOP M&A transactions are subject to specific IRS regulations, certain provisions in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) and are regulated by the U.S. Department of Labor. Conceived by Louis Kelso in the mid-1950s in part to foster employee ownership, ESOP M&A deals have evolved and are deliberately structured to comprehensibly address the potential risks inherent in a deal involving employees purchasing the owner’s equity securities in a business. Due to the nature of ESOP M&A deals, both the buyer and the seller are required to adhere to and document extraordinary prudency practices, a cut above, in my opinion, the M&A due diligence standards of care and customs and practices required in other M&A transactions.

Principal players on the seller’s side of an ESOP M&A deal include the following: the selling shareholders; legal advisors to sellers who are familiar with ESOP M&A deals, including applicable IRS and ERISA requirements; financial advisors to sellers who not only are familiar with structuring ESOP M&A deals but often conceived and pitched the transaction to the prospective selling shareholders, including proposing success fees as their compensation; and an ESOP Trust Committee, whose members are appointed by the company’s Board of Directors and who agree to act as fiduciaries on behalf of the ESOP beneficiaries.

Principal players on the buyer’s side include the following: a trust company with the requisite background and experience to serve as the Trustee in an ESOP M&A deal, which in part involves acting as a fiduciary on behalf of the ESOP beneficiaries in leading the ESOP M&A deal, including assuring reasonable buyer’s side due diligence; legal advisors to the Trustee who are familiar with ESOP M&A deals, including applicable IRS and ERISA requirements, and the performance of reasonable legal due diligence; financial advisors to the Trustee who are familiar with ESOP M&A deals and the performance of reasonable buyer’s side business and financial due diligence; and an experienced valuation advisor to the Trustee who will render a required valuation opinion in connection with the fairness of the specific terms and conditions negotiated by the Trustee and seller in the ESOP M&A deal.

In my experience in M&A deals, both the buyer and the seller must meet their individual due diligence responsibilities by adhering to the required due diligence standards of care and custom and practice. Buyer’s side due diligence, for example, is the investigation process performed by the buyer and its advisors to reasonably understand and evaluate, among other things, the accounting, financial, business and legal aspects of the target in order for the buyer to have a reasonable basis to believe in the accuracy and completeness of material information relied on in negotiating and approving the terms and conditions of the acquisition agreement and in closing the deal. The applicable standard of care in buyer due diligence is the performance of a reasonable investigation of potentially material information to ensure there is a reasonable basis to believe in the accuracy and completeness of information relied on by the buyer. The materiality standard dictates that information should be acquired if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider the information important in making an investment decision, or if the fact would meaningfully alter the total mix of information available.

Custom and practice of the required reasonable investigation is (i) to make inquiries reflecting a reasonable level of skepticism (that is, acting as the devil’s advocate), (ii) to follow up and reasonably resolve potential material red flags (that is, don’t unreasonably ignore potential material red flags), and (iii) to independently verify material information supplied by executives and advisors of the target (or other parties with potential conflicts of interests) on which the buyer intends to rely.

Professor Richard Puntillo’s Expert Witness practice draws on a unique background that combines a distinguished teaching career as a University of San Francisco finance professor with two decades of high-level executive experience in investment and commercial banking.

Professor Richard Puntillo’s Expert Witness practice draws on a unique background that combines a distinguished teaching career as a University of San Francisco finance professor with two decades of high-level executive experience in investment and commercial banking. Set forth below are detailed summaries of selected examples of cases where I served as an expert witness...

Set forth below are detailed summaries of selected examples of cases where I served as an expert witness...  Blog Categories:

Blog Categories: